This past spring I co-taught an upper-level MSU undergraduate class on Global Change Biology with fellow KBS Assistant Professor, Dr. Sarah Evans. Throughout the semester we discovered no shortage of urgent headlines to illustrate the wide range of hot-button topics we were discussing with our students.

This past spring I co-taught an upper-level MSU undergraduate class on Global Change Biology with fellow KBS Assistant Professor, Dr. Sarah Evans. Throughout the semester we discovered no shortage of urgent headlines to illustrate the wide range of hot-button topics we were discussing with our students.

Following the class, I am still signed up to receive all global-change related science news alerts and am inundated by worrying trends. This summer, we learned about the split of the Larsen C Iceberg from Antarctica, massive and ubiquitous declines of global vertebrate populations, and groundwater depletion leading to major shift and homogenization of Great Plains stream fish assemblages.

Needless to say, global change biology was on my mind as I prepared for this year’s annual meeting of the Society for the Study of Evolution held in Portland, Oregon in June (Portland skyline pictured above).

At this year’s meeting I had the honor of speaking in the American Naturalist Society’s Young Investigator Symposium. Despite the pressure of a symposium talk, by the time I arrived in Portland, I still did not have a coherent introduction or conclusions section of my talk – and this was not out of procrastination!

I was struggling with how much to frame my research in the context of fundamental evolution questions versus its relevance to biodiversity conservation and global change. I wanted to showcase my best work to an audience I perceived as being more interested in hearing about the basic and theoretical aspects of my research, yet, I felt increasingly motivated by and wanting to discuss the applied aspects with respect to pressing issues brought on by human-caused global change.

My talk was not until the last afternoon of the conference so I had a few days to soak in the meeting before making final changes, and this was fortunate, as it was hearing other great talks where I found my inspiration!

Many of the best-attended and best-presented talks I saw at this year’s meeting had global change related themes. Importantly, fundamental questions in evolutionary biology were still being addressed and answered, but in many cases, these questions were now being creatively applied to systems of conservation concern or processes associated with rapid environmental change.

Some highlights included Dr. Amy Angert (Biodiversity Research Centre, University of British Columbia) discussing her meta-analysis on how severely climate change is disrupting local adaptation – asking what happens when the “environmental rug” is pulled out from under locally adapted populations? Dr. Toby Fountain (Uppsala University) impressed on us the ability to understand the strength and genetic basis of inbreeding in small and isolated populations by sequencing 100 wolf genomes from a highly bottlenecked population.

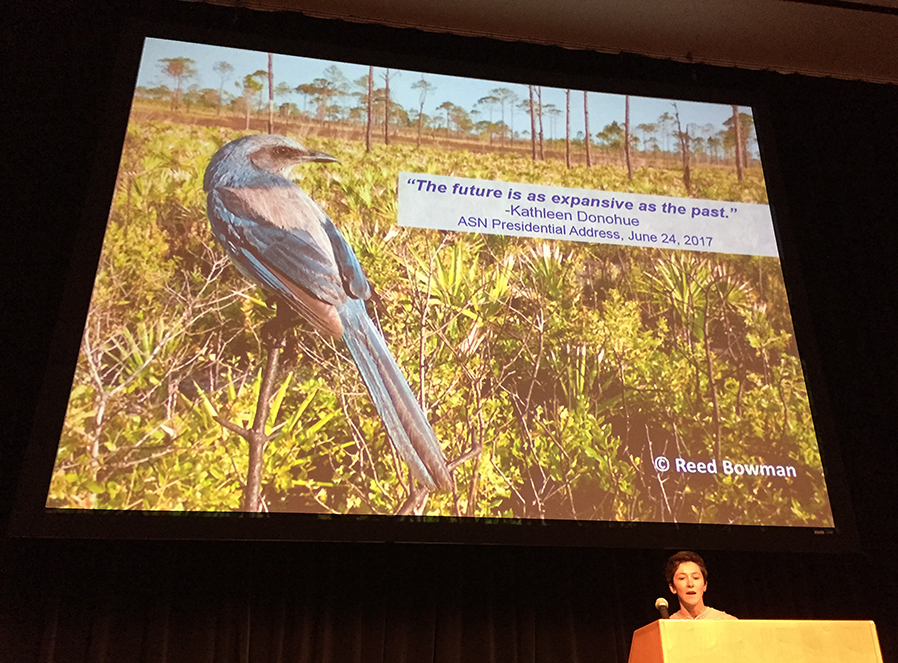

The talk that moved me to tears was Dr. Kathleen Donohue’s (Duke University) American Naturalist Society’s Presidential Address (available to watch on YouTube). This year marks the 150th anniversary for the American Naturalist’s Society and in her beautifully articulated talk Kathleen took us on a journey through the society’s mission and history, and told us how early ASN contributors led to the famous synthesis of genetics and evolution by natural selection, ultimately helping us understand that “given enough time, the improbable is the most plausible explanation for the diversity of life on earth”.

In other words, given that the earth is very, very old, if rare and improbable events that are few and far between, like small beneficial mutations, are given enough chances, some of them will take hold and even thrive. These rare genetic variants that take hold were then selected on and shaped over billions of years, eventually producing the spectacular diversity of life on our planet.

“This theory was formed to explain the distant past, well before humans were around to modify it.”

Kathleen then returned us to the present and challenged us to think about something that for me, speaks directly to my driving motivation for pursuing a career in research with a focus in evolutionary biology and conservation.

“We’re in a different time now.”

“How many of you think we still have all the chances, and still have all the time? Are these processes still completely external to us, beyond our influence?”

“When we shift our focus from the past to the present, suddenly time seems very short. Is there still enough time for evolution to accomplish what we want it to? Namely, prevent the next mass extinction.”

I knew immediately how I wanted to frame my talk after being pushed by Kathleen to consider this mismatch between what is needed for generation and maintenance of biodiversity (i.e., time and variation) and the fast-paced depletion of those conditions in our world today.

“With fewer chances, less time, things moving around with newfound mobility, as environments themselves are changing so rapidly and becoming less habitable, and less matched to adaptations. As all of these processes are speeding up, and the heartbeat of the landsnails are slowing down, how do we modify our most fundamental [evolutionary] theories, given that they were founded on assumptions of improbability and endless time?”

My research deals with evolution on contemporary timescales – I study what happens to populations when they become small and fragmented, and how to reverse declines by altering connectivity and providing genetic variation through assisted migration, a controversial management strategy that has been termed ‘genetic rescue1’. While this work does address a fundamental debate in evolutionary biology on whether gene flow plays a primarily constraining versus diversifying evolutionary role, my goal is also to provide useful guidelines and to practice boots-on-the-ground conservation and management of wild populations.

By gaining an improved understanding of how to manipulate interactions between the evolutionary forces of gene flow, genetic drift, and selection, my hope is that we may be able to buy time and even facilitate adaptation for threatened populations despite the rug being pulled out from under them.

Sarah Fitzpatrick is a KBS Assistant Professor in MSU’s Department of Integrative Biology. She was a 2017 recipient of the American Society of Naturalists’ Young Investigator Award. Watch her ASN Young Investigators symposium talk on Youtube.

1Whiteley, A. R., S. W. Fitzpatrick, W. C. Funk, and D. A. Tallmon. 2015. Genetic rescue to the rescue. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 30:42–49.

A legacy of conservation; a commitment to sustainability.

3700 E. Gull Lake Drive

Hickory Corners, MI 49060

(269) 671-5117

info@kbs.msu.edu