I spent the summer of 2017 at the Kellogg Biological Station (KBS) studying climate change and predation among aquatic organisms. This 11-week research experience was as eventful and influential as it could’ve been. It cemented my ability to conduct meaningful research, gifted me the opportunity to explore the beautiful state of Michigan, and served as a stepping stone towards a much-anticipated future in climate research.

I spent the summer of 2017 at the Kellogg Biological Station (KBS) studying climate change and predation among aquatic organisms. This 11-week research experience was as eventful and influential as it could’ve been. It cemented my ability to conduct meaningful research, gifted me the opportunity to explore the beautiful state of Michigan, and served as a stepping stone towards a much-anticipated future in climate research.

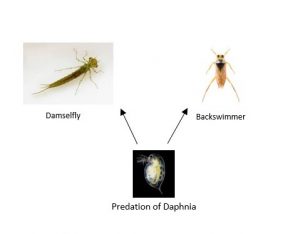

My experience at KBS began in late May, when I arrived at the Kalamazoo airport, and was driven past acre after acre of farm land toward KBS. By the end of my first day, I met my mentor, Ph.D. student Laura Twardochleb. After all the welcomes and introductions were over, I buckled down to learn everything about my mentor’s research, looking at how climate change will affect food webs involving predatory backswimmers, damselflies, and prey Daphnia.

I spent the first half of my research experience helping with her project. I sank into the warm pond water at the Lux Arbor Reserve, Southwestern Michigan, protected by my waders as I counted damselflies caught in traps above the water. These hot, muggy summer days were very rewarding, as I learned how to conduct population counts and plant abundance surveys. We always ended the day in the cool air-conditioned lab, where I patiently prepared for my own research project that was to follow.

The second half of my summer was spent on my research project, investigating the effects of temperature on the movement rates of the predatory backswimmers and prey Daphnia. Climate warming can determine species movement rates, which can then affect predation rates and even food web stability.

Finding the temperatures at which Daphnia and their predators move significantly faster allows for a better understanding of how predation rates will change with rising temperatures. I was excited and determined to carry out this project, knowing how important it was to understand exactly how movement rates would affect predator-prey relationships, and help predict population modelling.

I planned and carried out the same methods each day: putting Daphnia collected from the Lux Arbor ponds into containers, letting them acclimate in growth chambers set at different temperatures, and videotaping their movements. I used the video recordings to track their velocity, using an online video imaging software.

After weeks of experimentation and video analysis, I had all my data, and I was thrilled with my results! Using statistical testing, I found that Daphnia moved significantly faster at higher temperatures. I also found that Daphnia moved the fastest at 37 °C, and that they started to die at temperatures higher than that.

Lastly, I found that there was a lot of variability in velocity at higher temperatures, which could be the result of heat stress, or different thermal peaks among individuals in the population. This suggests that changing predation rates are the result of changing movement rates. As temperatures in Michigan pond ecosystems will likely increase from their peak of 32°C up to as high as 39°C over the next century, determining how predator and prey movement rates are changing is crucial towards developing more accurate population models going forward.

Along with the knowledge and insight I picked up from my research, my summer at KBS was full of other highlights too. Each month was packed with Professional Development seminars, where I was introduced to effective scientific communication skills, taught about fisheries management in Michigan, and even learned how to remove nasty ticks.

On the recreational side of the summer, we were given a behind-the-scenes tour of the Chicago Field Museum, where I was blown away by thousands of preserved organisms and exhibits on evolution. We also spent several weekends travelling, where I felt the gentle winds of Lake Michigan for the first time, and hiked sand dunes larger than my house at Sleeping Bear Dunes.

My experience at KBS was the perfect mix of independent research and career development, riddled with new and exciting experiences around Michigan. I learned so much about climate change issues relating to community structure in aquatic ecosystems, and discovered what it’s like to work in a full-time research lab. I feel much more confident in my ability to affect positive change in the field of climate science, and can’t wait to build on my research that I began here.

Tyler Treakle is a senior at The College of William & Mary double-majoring in Biology & Environmental Economics. He participated in the KBS REU (Research Experiences for Undergraduates) program during the summer of 2017.

Tyler Treakle is a senior at The College of William & Mary double-majoring in Biology & Environmental Economics. He participated in the KBS REU (Research Experiences for Undergraduates) program during the summer of 2017.

A legacy of conservation; a commitment to sustainability.

3700 E. Gull Lake Drive

Hickory Corners, MI 49060

(269) 671-5117

info@kbs.msu.edu