A collaborative study by KBS assistant professor Sarah Evans, KBS graduate student Robert Logan, Cary Institute researcher Kathleen Weathers and Bard College professor Eli Dueker exploring the biology of fog was recently featured in The Atlantic.

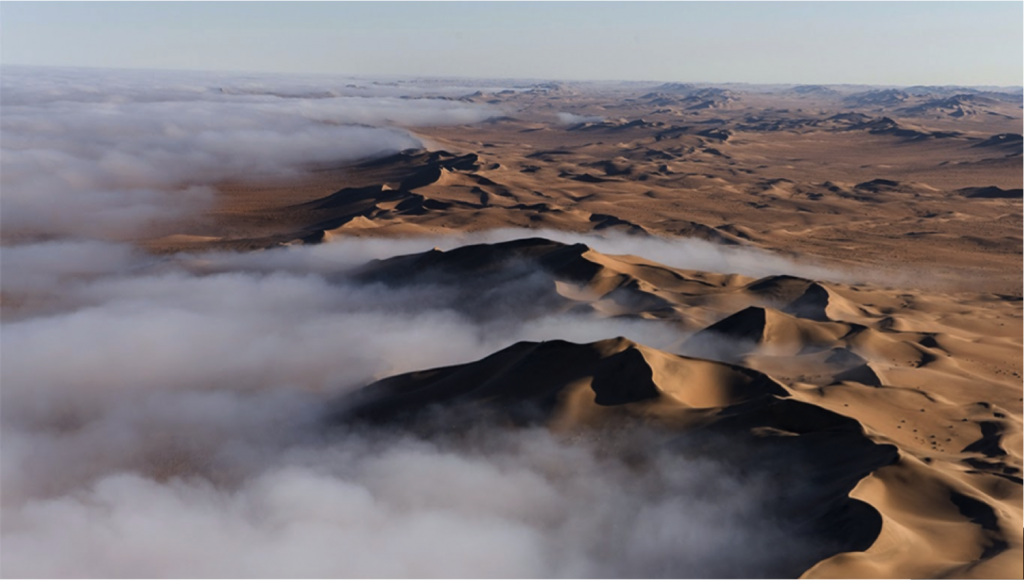

For being one of the driest places on the planet, the Namib desert has a fascinating relationship with water. Its fog-covered coast is the site of a previously unstudied transfer between land and sea.

It’s been understood that animals and plants in the desert rely on the fog for moisture and nutrients, but until now, it was unconfirmed that the fog was carrying more than that. Marine microbes are migrating inland, using the fog as a form of public transportation.

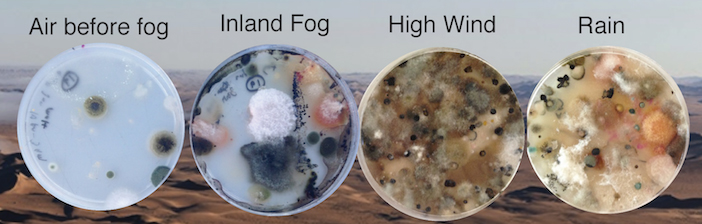

KBS assistant professor Sarah Evans and graduate student Robert Logan collected samples of fog in the Namib. They collected some fog directly on petri dishes, so they could grow living microbes. They also filtered some fog water so they could collect microbial DNA, which they sequenced back at KBS.

During a visit to KBS as a seminar speaker, fog researcher Kathleen Weathers told Evans that Bard College professor Eli Dueker was conducting a similar study on the foggy coast of Maine. This sparked a collaboration between Weathers, Dueker, Evans and Logan that resulted in a publication in Science of the Total Environment on the biology of fog.

The team found that their samples from both Maine and the Namib contained a diverse microbial community, featuring a mix of both soil-based and ocean-based microbes. As one might expect, the proportion of marine to terrestrial microbes shifts depending on how close to the ocean the fog is – more marine microbes directly on the coast in Maine, fewer 30 miles inland in the Namib desert.

“On the journey from the ocean to the land, microbes not only survive, but change during transport,” said Dueker. “Fog itself is a novel, living ecosystem.”

Microbes that ride fog droplets tend to live longer than those that live in ordinary air, and are more readily safely deposited on land. The presence of fog changes the land’s existing microbial community, shifting the fog’s benefits and detriments for plants and animals.

Most of the microbes that the researchers found in the fog are totally harmless to humans, but knowing that fog is a conduit for microbes does present possibilities for research on fog-borne pathogen transfer. This could be especially significant for fog around polluted or otherwise contaminated areas.

A legacy of conservation; a commitment to sustainability.

3700 E. Gull Lake Drive

Hickory Corners, MI 49060

(269) 671-5117

info@kbs.msu.edu