Science is often a series of failures that teach us how to succeed. After a first field season riddled with messes, graduate student Sean Griffin is making a beeline toward his research on pollinators in his second year of field work.

Griffin, a student in Nick Haddad’s lab, is interested in bee colonization of new habitats, a process about which little is known. Going into his first year of field work, he had no idea what to expect from his landscape-scale colonization experiment in South Carolina.

Almost everything that could have gone wrong, did.

Almost everything that could have gone wrong, did.

He wanted to release native bees into his landscapes – and couldn’t find anywhere to get them from.

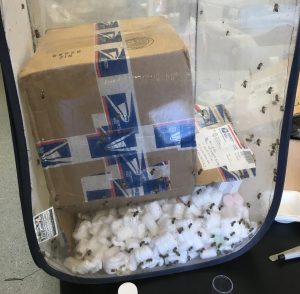

The non-native early spring nesting species of bees he did procure got lost in the mail and emerged from hibernation in a post office, escaping their packaging (pictured at right).

He was still able to release them, but of the 3000 he started with, only a single bee colonized the nest boxes for his experiment.

He decided to release leafcutter bees next – a resilient, affordable and accessible species (pictured at right). He didn’t originally want to release them in the summer because of the heat and limited blooming potential of flowers – and his first round of leafcutter bees all died due to an unusual overnight freeze.

He released another round of leafcutter bees into the experimental landscapes, not knowing if anything would come of his efforts. He decided to step away for a little while.

He released another round of leafcutter bees into the experimental landscapes, not knowing if anything would come of his efforts. He decided to step away for a little while.

“I was like, ‘This is not going to work, I need to just clear my mind.’ So I went on vacation for a week, came back, and all of the leafcutters were all over my nest boxes!” he said.

He doesn’t know how that summer would have gone if it hadn’t been for his advisor.

“I’m really appreciative of Nick, because I’m a serious pessimist, and Nick is the most optimistic person I’ve ever met,” he said. “He was pushing me the whole time to just do it, even though it’s a crazy project and no one knows if this kind of thing works on these scales, and it worked! I just had to find the right bee, and do the experiment a few times.”

He was pleasantly surprised that he got the data he needed. The mishaps of the South Carolina field season informed all of Griffin’s choices for his research this summer at KBS.

“This field season, I was able to hit the ground running, use the right bee, and put them out at the right time,” he said.

For the most part, everything this summer has gone right. The bee populations he’s released at the GLBRC and LTER sites at KBS have survived and are colonizing the nest boxes he set up.

For the most part, everything this summer has gone right. The bee populations he’s released at the GLBRC and LTER sites at KBS have survived and are colonizing the nest boxes he set up.

The only thing that hasn’t gone according to plan is his use of a fluorescent dye powder – thankfully, a nonessential part of the experiment. He and Haddad had hoped the bees would step in the powder on their way out of the release boxes (pictured at right), making their dispersal patterns trackable.

The first time checking the nest boxes at night showed that the bees’ fluorescent dye wasn’t as strong of an indicator as they had anticipated. The white backgrounds of the nest boxes made it easier to see the bees during the day, but the bright background’s bouncing of his UV light made it impossible to see much, if any, of the dye on the bees at night. Still, flecks of the powder are visible on the nest boxes, so he’s able to get at least a small amount of data on where bees are coming from.

There will always be bumps in the road, but Griffin is learning from the obstacles he finds on his way.

“I’ve had – like any scientist that’s been doing work for a few years – a lot of projects fail,” he said. “But you always get something out of it – just something different than you’d expected.”

“I’ve had – like any scientist that’s been doing work for a few years – a lot of projects fail,” he said. “But you always get something out of it – just something different than you’d expected.”

He’s able to keep moving forward despite obstacles thanks to encouragement from his advisor and labmates, as well as his passion for bees.

“Bees do a huge amount of pollination of crops, up to 90% of the world’s plant species,” said Griffin. “They do a lot from an ecosystem service point of view. But my interest is also in preserving rare bees, which we don’t know much about in comparison to other species like rare butterflies.”

Because bees are small and hard to track across wide dispersal areas, it’s difficult to know which bee species are in need of conservation work. Well-studied species of bees like bumblebees have been added to the endangered species list in the past few years, but there are hundreds of bee species in the United States alone that are declining and aren’t being studied.

“I see my work as conservation-focused; we don’t want these species to die off,” he said. “Because we don’t know enough about them at this point, we want to create habitats and practices that will protect as many bees as possible.”

“I see my work as conservation-focused; we don’t want these species to die off,” he said. “Because we don’t know enough about them at this point, we want to create habitats and practices that will protect as many bees as possible.”

His work focuses on issues impacting bees that often go unstudied.

“Most conservation efforts focus entirely on resources for bees, like picking pollinator-friendly flower mixes, but the more we learn about bee natural history, the more we find that nest sites might actually be more limiting for them,” he said.

He’s investigating how flower availability, and as many other factors as are possible to look at, affect bee decision-making about where to nest. While the field season isn’t over yet, this summer’s preliminary data seem promising, and for Griffin, conservation is something worth persevering for.

Blog written by Bethany Bohlen, header image by Ninna Biondo, post office image courtesy of Sean Griffin, all other images by Bethany Bohlen.

A legacy of conservation; a commitment to sustainability.

3700 E. Gull Lake Drive

Hickory Corners, MI 49060

(269) 671-5117

info@kbs.msu.edu