The fungi that live in the seeds and in the leaves of plants play a part in the overall health and productivity of their host plants. That role isn’t well-defined despite big implications of that understanding for farmers and other land managers.

A new paper from W.K. Kellogg Biological Station researchers adds to a growing body of knowledge about the microbial communities that live on and in the plants around us.

Lukas Bell-Dereske, formerly a postdoctoral researcher at KBS now at the Institute of Microbiology in the Czech Academy of Sciences, and Sarah Evans, associate professor at KBS in Michigan State University’s departments of Integrative Biology and Microbiology and Molecular Genetics, studied the transmission of fungi to switchgrass (Panicum virgatum), a perennial bioenergy crop, to understand the importance of environmental transmission of the fungi, such as rain, relative to maternal transmission (via a seed).

Their paper, “Contributions of environmental and maternal transmission to the assembly of leaf fungal endophyte communities,” was recently published in the Royal Society’s biological sciences journal.

Roadmaps for microbial communities

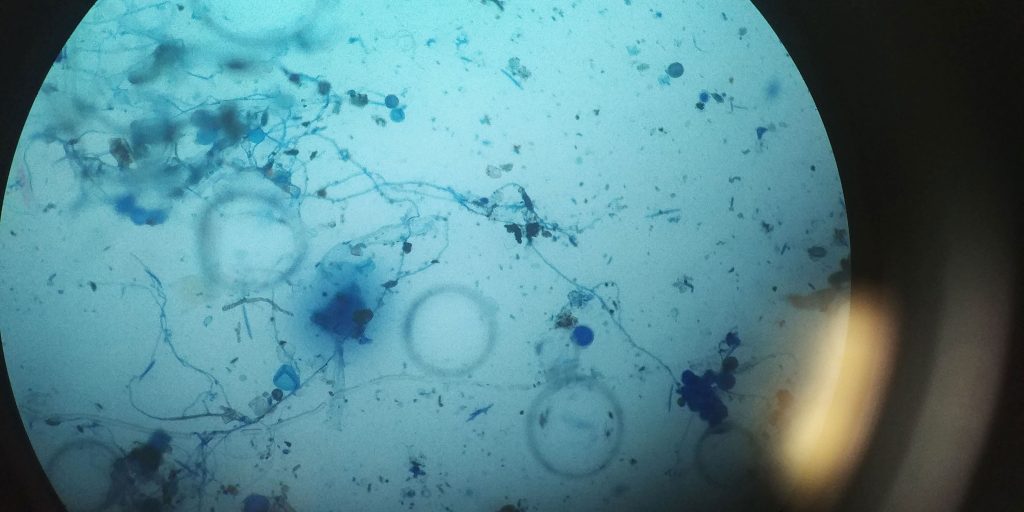

To study the transmission of leaf fungal endophytes, or LFEs, Bell-Dereske and Evans gathered data from rain collection and seed fungi in switchgrass plants in greenhouse and field experiments at KBS’s Marshall Farm, then used genetic sequencing to track the LFEs.

They found that rain and other means of environmental transmission were a major source of the fungi that live in switchgrass leaves—some 65%. But seed fungi made up more than 25% of the LFE species in mature plants. That surprised the researchers because the switchgrass plants were more than a decade old. This suggests that seed fungi can be long-term contributors to a fungal endophyte community.

And of course, not all fungi are detrimental to plants. Bell-Dereske and Evans also found that while rain is a major source of pathogens, it also can contribute beneficial, or mutualistic, fungi to an endophyte community.

“This research has implications for people interested in the utilization of microbial communities to address current and future challenges for the sustainable growing of crops,” said Bell-Dereske. “For these plant microbial communities to be utilized, we must understand how they assemble and what types of microbes may invade the beneficial communities, disrupting our efforts.”

“In addition,” he added, “as we begin to inoculate crop species with novel microbial communities, we must understand how these novel communities may spread to surrounding plant species.”

A legacy of conservation; a commitment to sustainability.

3700 E. Gull Lake Drive

Hickory Corners, MI 49060

(269) 671-5117

info@kbs.msu.edu